Vietnam veteran and SEMO alum publishes memoir of time at war

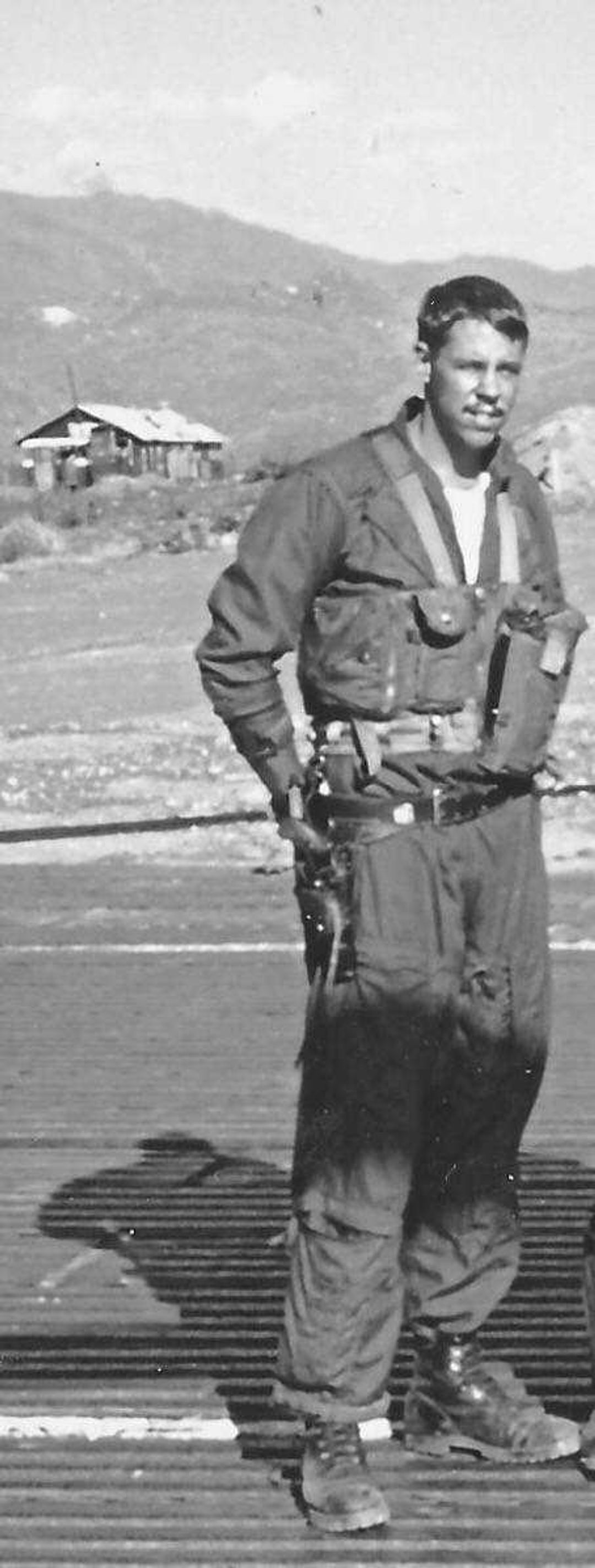

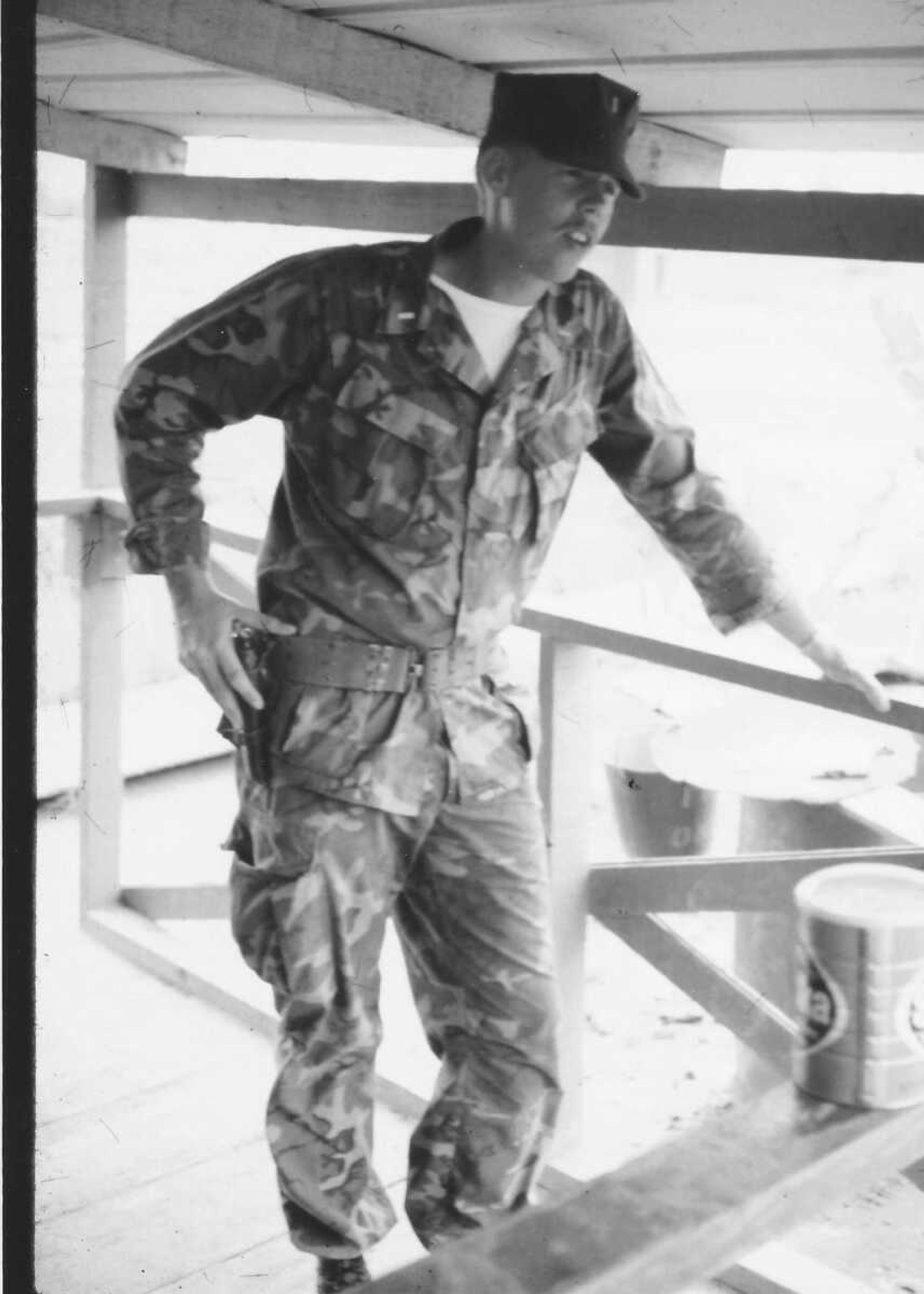

Vietnam helicopter pilot Lt. Col. Harold Walker Walker went from “frat-rat,” to Marine, to undercover law enforcement agent, to private investigator, to where he is now at 73, an author.

Harold Walker had plans of becoming a teacher before being drafted into the Vietnam War just months before graduating from Southeast in 1967.

Instead, the adrenaline of his days hovering over battlefields as a helicopter pilot led him to a life more fitting of a movie script. Walker went from “frat-rat,” to Marine to undercover law enforcement agent to private investigator to where he is now at 73, an author.

In his most recent work of literary non-fiction “The Grotto Book One: Phu Bai, Vietnam 1969-1970,” Walker tells the story of his early days in Vietnam, the things he saw there and the bond formed among soldiers.

Walker’s life began as it did for many natives of Southeast Missouri. He grew up hunting and fishing on the floodways of the Mississippi River before enrolling at Southeast. He joined Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity because his brother was a founding member and spent his years in college chasing after the woman who is now his wife. But as the body count grew in Vietnam, he soon realized the need to grow up fast.

Walker said his “school-boy” status allowed him to keep from joining up when the government first came calling, but they were “running short on warm bodies” and he was one of the few remaining Bootheel men eligible for the draft.

After flight school he and several other Southeast students, from various fraternities and hometowns, found themselves in a war that had reached a turning point. The Tet Offensive — a last ditch all-out effort by the North Vietnamese defined by ambush and guerilla attacks throughout South Vietnam — catalyzed a de-escalation of American involvement, which went on throughout the war’s official end in 1975, and was no less bloody.

He compared his time at the forward-base fondly referred to as the “Mossy Grotto” (the book’s namesake), to being a “prospect in an outlaw motorcycle gang.”

“It was like an 1880s mining camp with that military twist, more ‘Mad Max’ than anything else,” he said. “Just a tough bunch of people.”

Walker worked closely with a wild bunch of reconnaissance forces, who were responsible for “ambushing the ambushers.”

“They wouldn’t wash with soap, because they were afraid they’d be smelled when they were in the jungle,” he said. “They were the real, real bad guys. It got to the point where the NVA had a bounty on their heads.”

Rowdiness, he said, was a characteristic of the base.

“There were fights in the club, there was all kinds of drinking,” he said. “They had a rule, you know, 12 hours between drinking and flying, and anyone can say what they want to, but I think a lot of guys thought it was 12 feet between drinking and flying.”

The massive aircraft Walker flew, the tandem rotor CH-46 (which have since taken a back seat to the BlackHawk helicopter), were responsible for wartime tasks such as medical evacuations, resupplying troops and bringing soldiers into battle.

Walker said he witnessed the bravery of those men on the ground countless times and in his mind, the bar for what makes a hero is set very high as a result. He defined the word as knowing you could be killed, but for the protection or rescue of others, going forward anyway.

“I saw that from a helicopter, I saw it in guys that I was getting out of battles,” he said. “I really am humbled to be in their presence.”

From the cockpit, flanked by a convoy of other aircraft (per Marine Corps procedure), cruising in on a location marked by billows of colored smoke, Walker said he often felt like more of an observer of the war than a participant.

“Between me and the battle was plexiglass,” he said. “Those guys out there, there wasn't anything between them and the battle but a bayonet.”

He had pilot friends who were shot down multiple times, who saw the soldiers within their aircraft burned alive, or peppered with enemy fire to the point that blood ran down the ramp.

“Those guys didn’t even have a chance to get in the fight, and it was dead and dying right there,” he said. “And we never hesitated, helicopter guys, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, never hesitated to go in because you’re thinking ‘He can do that, then I can do this.’”

Walker said he has always had a strong appreciation for non-combat veterans, too — helicopter mechanics and the like, who worked day and night for years without taking a day off.

“From the tip of the spear to the butt of the weapon, that whole line of veterans is necessary in order to go to war,” he said.

After returning from Vietnam, Walker pursued his Master’s degree in administration at Southeast and worked for two years as a highschool principle. But his military experiences led him toward a career in law enforcement.

He was recruited by ATF in the early 1980s, going undercover on the Southside of Chicago, commissioned to find the sources of illegal firearms and explosives and remove them from the environment. This effort to clean up the streets was an initiative of former President Richard Nixon’s “Concentrated Urban Enforcement,” implemented by President Gerald Ford. Walker described his first exposure to the city’s underground world of crime as entering Hell.

“It was a remarkable experience,” he said. “I felt like I was actually involved in the war then, as opposed to what I did in Vietnam. As a helicopter pilot you were in the war, but you really weren’t out there fighting with the guys with an M16 in your hand. Now I felt like I was doing my part.”

Walker had remained in the Marine Corps reserves after his time in Vietnam and was called upon again during Operation Desert Storm. He performed countless evacuations of troops and civilians during Mount Pinatubo’s massive volcanic eruption near a military base in the Philippines in 1991. He said his next book, “Tubo: Gangsters in Paradise,” will detail those years as a “Huey” pilot.

He retired from the Marine Corps reserves in 1996 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

His first book, “Murder on the Floodways,” has received some critical acclaim, drawing comparisons to Truman Capote’s true-crime classic “In Cold Blood.” Walker said the subject matter — the double-killing of two Bootheel hell-raisers that took place on his family farm — was a story he had told and retold throughout his life before writing it down. The discovery of a “car full of blood” as a 12-year-old boy, Walker said, was his first exposure to violent death and created an image that always stuck with him. His experience as a private investigator in the years following his work with various law enforcement agencies, helped him gather a multitude of information and first hand accounts in a four-year investigation of the incidents.

In a write-up for the Arkansas Review, Southeast professor of history Dr. Adam Criblez called “Murder on the Floodways” a beautifully written slice of Americana.

Both of Walker’s books “Murder on the Floodways” and “The Grotto Book One: Phu Bai, Vietnam 1969-1970” are available on Amazon or haroldgwalker.com.